So much more than a

classic

Directed by the legendary Robert Wise, “The Day the

Earth Stood Still” is one of the best

science fiction films of all time.

Adapted

from the sublime short story “Farewell to the Master” by Harry Bates, this iconic movie was released in 1951, when the threat of global nuclear obliteration was at its frenzied apex. Since then, the story has not lost one iota of its urgency and relevance. In fact, the more than half century that has passed since the film's premiere has

made its final warning even more poignant.

Humanoid

alien Klaatu, subtly underplayed by Englishman Michael Rennie, lands his

flying saucer in Washington DC, unintentionally instigating a worldwide wave of

panic. Though his purpose is peaceful,

Klaatu is accidentally shot by a jittery soldier. When his requests to address prominent international leaders about his mission are met with snorts of derision, Klaatu decides to magically vanish from his

military hospital bed and see for himself if the everyday citizens of Earth are more open-minded and less fearful.

With the authorities searching desperately to find their escaped prisoner from another world, Klaatu befriends a young boy named Bobby, whose youthful enthusiasm is still boundless

despite his father’s passing in World War II.

Klaatu knows something about the futility of armed conflict, and he enlists

Bobby to help him find someone who will hear what Klaatu has to say: someone who

will listen without prejudice.

So

begins the lead-in to one of my most cherished moments in all of

cinema. At Bobby’s suggestion, he and

Klaatu pay a visit to Professor Barnhardt, delightfully portrayed by Sam

Jaffe. Finding the professor absent from his

office, Klaatu leaves a calling card by solving a complex mathematical equation

on the professor’s chalkboard. This

earns him a private meeting, and when Klaatu arrives, he reveals his identity

to the professor’s astonishment and joy.

Klaatu

puts his life in Professor Barnhardt’s hands, and there is no question about

the answer. The professor quickly walks to his

office door and tells the MP that he can go because he knows this man. Klaatu is pleased and says: “You have faith,

Professor Barnhardt.” Barnhardt replies: “It

isn’t faith that makes good science, Mr. Klaatu, it’s curiosity.” Is that not the argument of the age? Doesn’t it so succinctly encapsulate the struggles of all human history?

At

last we come to the one line of dialogue that utterly undoes me every time. Professor Barnhardt bids Klaatu to

sit down and fixes him with a piercing gaze of intense longing and says: “There

are several thousand questions I should like to ask you.” I am in tears at this

heartfelt plea because only the professor understands the colossal potential of what this

meeting represents. Barnhardt is the one person on the

entire planet who sees Klaatu for what he is: the greatest single source of

knowledge that humankind has ever encountered.

Everyone

else on Earth has been mentally hobbled by the hysteria spread through

radio and television. They

have stopped thinking critically and calmly.

Instead, the murmuring mob reacts like children crowded round a campfire, shivering with fright at the scary stories being spun with

reckless abandon. Ignorance looms like

the advancing twilight. Only Professor Barnhardt, with

his intellect and healthy ego is immune to the subconscious mewling of the lizard brain. His aching desire to learn

is a light in the darkness and serves as a shining example to us all.

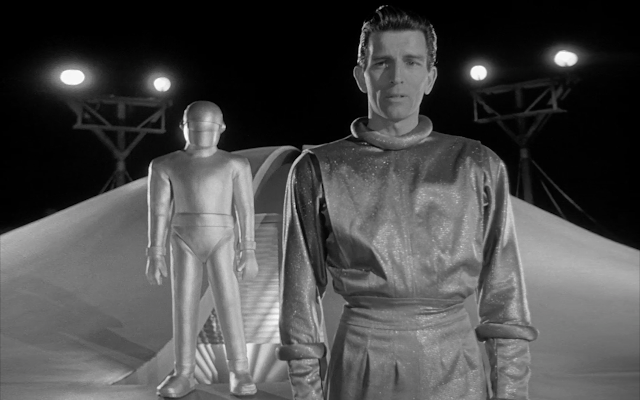

Klaatu's final speech to the scientists and other luminaries gathered by Professor Barnhardt is a jaw dropper. Standing proud and stern on the hull of his ship with the imposing Gort at his back, Klaatu issues an ultimatum of total annihilation should we extend our fledgling atomic activities beyond our little globe. No threat to the security of the other worlds will be tolerated. Yet, there is still hope, for Klaatu promises that the Earth will be spared if we can finally put away childish things. The choice is ours, and if we choose wisely, the entire galaxy will be waiting for us.

“The Day the Earth Stood Still” is not only one of the best films of its genre; it is one of the greatest of all time. It confronts us with our greatest failings and also celebrates our fondest aspirations. It shows us who we are and what we would like to be. It is a dream from the past about a future we could all share if we could only open our hearts and minds wide enough to see the stars and the dazzling destiny that awaits us. When we can finally create the sense of unity that enables us to love our differences and leave our fears behind, then we can truly begin to live.